Are You the Victim of This Wall Street Scam?

|

It’s a scam that few advisers talk about and most investors don’t even think about: The conflicts, bias, payola and cover-ups behind most of the ratings you get from Wall Street.

I’m talking about “buy, “sell” or “hold” ratings on your stocks and mutual funds … credit ratings on your bonds … insurance-company ratings … and ratings assigned to tens of thousands of companies and investments of all kinds.

The big problem: The bias is virtually never in your favor. It’s almost invariably in favor of the companies that issue stocks and bonds or sell the insurance polices.

That means the overwhelming bulk of your investments could be overrated!

This is not universal, mind you. There is a minority of analysts who are truly independent. And there are always going to be select stocks that are underpriced regardless of whether they get accurate ratings or not. But …

When It Comes to Bias, It’s the BIG Wall Street Firms

That Are Typically the Worst Offenders.

Hard to believe?

Then consider this: Just a few years ago, Wall Street’s leading rating agencies, including Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch, quietly took a series of steps to tacitly ADMIT their ratings and research are indeed biased.

That’s right. They went through all their advertising and removed the word “independent.” (For proof, see this Harvard Business School study: “Implied Materiality and Material Disclosures of Credit Ratings.”)

That’s unfortunate.

When the integrity of the ratings is compromised, it creates extra risks for everyone — individual investors, professional investors and even non-investors.

And those risks are of particular concern when the market is surging, investors become complacent, and many players let their guard down.

The reason is simple: If something is overrated, it is probably overpriced.

It attracts buyers who think it’s a good investment. But as soon as the naked truth is revealed, or the inflated rating is downgraded, investors run in panic; and the resulting price declines can deliver surprising losses.

In the long term, this could be one of the greatest silent killers in your portfolio. And whether you use ratings or not, it’s essential that you fully understand how it came about and how you can avoid the risks.

My Personal Experience with This

Sorry Saga Begins in the 1980s …

I had already been in the been rating the safety of the nation’s banks for over a decade, and my father, Irving Weiss, who started analyzing banks in the late 1920s, was an octogenarian.

|

One afternoon, I told him our Weiss Ratings division was planning to start rating insurance companies.

I showed him some industry charts on my computer screen and asked his opinion.

“Check out First Executive (the parent of Executive Life Insurance),” he said. “Fred Carr’s running it — the guy they literally kicked out of Wall Street a few years ago. He’s trouble, and he’s knee-deep in junk bonds. Follow the junk and you will find your answers.”

We did. We bought the entire database of insurance companies that had recently been made available for the first time by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

We built a computer model free of bias either for or against the companies.

And we found quite a few life insurance companies that were loaded with junk bonds, one of which was First Capital Life, to which I gave a D- rating. I was generous. The company should have gotten an F.

But within days of my widely publicized warnings on First Capital Life, a gaggle of the company’s lawyers and top executives flew down to our office. They ranted. They raved. They swore they’d slap me with a massive lawsuit and put me out of business if I didn’t give them a better rating.

“All the Wall Street ratings agencies give us high grades,” they said. “Who the hell do you think you are?”

I politely explained that we never let personal threats affect our ratings. And unlike other rating agencies, we don’t accept a dime from the companies we rate.

“I work for individuals,” I said, “not big corporations. Besides,” I continued, opening up the company’s most recent quarterly report, “your own financial statements prove your company is in trouble.”

Insurance Company Executive:

“Weiss better shut the @!%# up!”

That’s when one of them delivered the ultimate threat: “Weiss better shut the @!%# up,” he whispered to my associate, “or get a bodyguard.”

We did neither. To the contrary, we intensified our warnings. And within weeks, the company went belly-up just as we’d warned — still boasting high ratings from major Wall Street firms on the very day it failed.

In fact, the leading insurance rating agency, A.M. Best, didn’t downgrade First Capital Life to a warning level until five days after it failed. Needless to say, it was too late for policyholders.

It was a grisly sight — not just for policyholders, but for shareholders as well: The company’s stock crashed 99%, crucifying millions of unwitting investors. Then the stock died, wiped off the face of the earth.

Three of the company’s closest competitors also bit the dust. Unwitting investors — who did not have access to our ratings — lost $4 billion, $4.5 billion and $13 billion, respectively.

Fortunately, those who had seen our ratings were ready. We warned them long before these companies went bust. Nobody who heeded our warnings lost a cent.

In fact, the contrast between anyone who relied on our ratings and anyone who didn’t was so stark, even the U.S. Congress couldn’t help but notice.

They asked: How was it possible for Weiss — a small firm in Florida — to identify companies that were about to fail, when Wall Street told us they were still “superior” or “excellent” right up to the day they failed?

To find an answer, Congress called all the rating agencies — S&P, Moody’s, A.M. Best, Duff & Phelps (now part of Fitch) and Weiss Research — to testify.

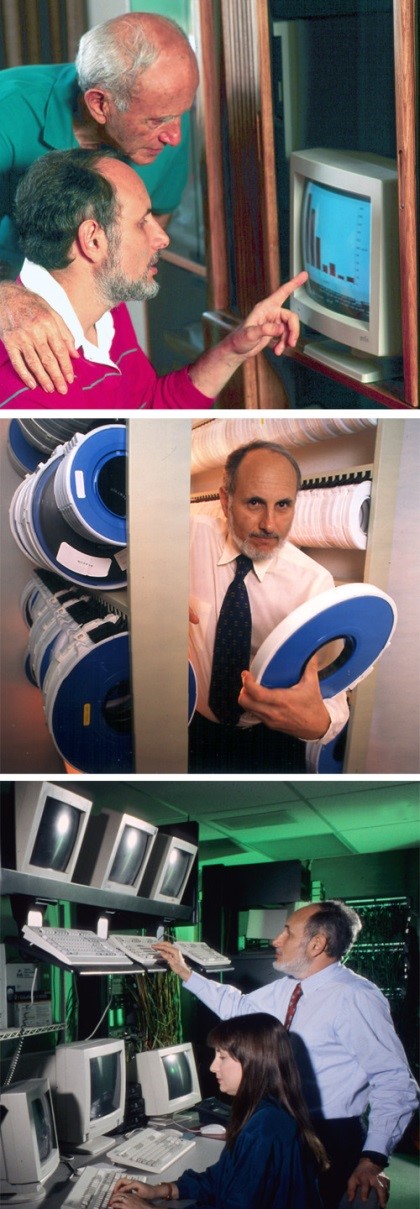

|

| Click on image to view GAO report. |

But I was the only one among them who showed up. So Congress asked its auditing arm, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), to conduct a detailed study on the Weiss Ratings in comparison to the ratings of the other major rating agencies.

Three years later, after extensive research and review, the GAO published its conclusion: Weiss beat its leading competitor, A.M. Best, by a factor of 3-to-1 in forecasting future financial troubles. The three other Wall Street firms weren’t even competition.

But the GAO Never Answered

The Original Question — WHY?

I can assure you it wasn’t because we had better access to information than our competitors. Nor were we smarter than they were. The real answer was contained in one, four-letter word — bias.

To this day, the other ratings agencies are paid very large fees by the companies for the ratings; their ratings are literally bought and paid for by the companies they rate.

These conflicts and bias in the ratings business are no trivial matter. To make money in today’s investment world — and to avoid unexpected losses — you must understand them. And you must know how to sidestep them.

In fact, I feel this is so important, I have decided to dedicate a special series of articles to the subject, dedicating today’s to one of four ratings fiascos of modern history ...

Ratings Fiasco #1

How Deceptive Ratings Entrapped 1.9

Million Americans in Failed Insurance

In the early 1980s, insurance companies had guaranteed to pay a high yield to investors of 10% or more. But the best they could earn on safe bonds was 8%, 7% or 6%. They had to do something to bridge that gap — and quickly. So how do you deliver high guaranteed yields when interest rates are going down?

Their solution: Buy the bonds of financially weaker companies.

Consider, for a moment, what bonds are, and you’ll understand the situation.

When you buy a bond, all you’re doing, in essence, is making a loan. If you make the loan to a strong, secure borrower, you won’t be able to collect a very high rate of interest. If you want a truly high interest rate, you need to take the risk of lending your money to a borrower that’s riskier — maybe a start-up company, or perhaps a company that’s had some financial difficulties.

What’s secure and what’s risky? In the corporate bond world, everyone has generally agreed to use the standard rating scales established by the two leading bond rating agencies — Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s. The two agencies use slightly different letters, but their scale is basically the same — triple-A, double-A, single-A ... triple-B, double-B, single-B ... etc.

If a bond is triple-B or better, it’s investment grade, relatively secure. If the bond is double-B or lower, it’s speculative grade. It’s not garbage you’d throw into the trash can. But in the parlance of Wall Street, it is officially known as junk. And that’s what many life insurance companies started to buy in the 1980s — junk.

They bought double-B bonds. They bought single-B bonds. They even bought unrated bonds that, if rated, would have been classified as junk.

Until this juncture, their high-risk strategy could be explained as a stop-gap solution to falling interest rates. But unbelievably, a few insurance companies — such as Executive Life of California, Executive Life of New York, Fidelity Bankers Life and First Capital Life — took the concept one giant step further: Their entire business plan was predicated on the concept of junk bonds from day one.

The key to their success was to keep the junk bond aspect hush-hush, while exploiting the faith people still had in the inherent safety of insurance.

But to make the scheme work, they needed two more elements: The blessing of the Wall Street ratings agencies and the cooperation of the state insurance commissioners, many of whom had worked for — or would later join — the companies.

The blessing of the rating agencies was relatively easy. Indeed, for years, the standard operating procedure of the leading insurance company ratings agency, A.M. Best & Co., was to work closely with the insurers.

If you ran an insurance company and wanted a rating, the deal that Best offered you was very favorable indeed. Best said, in effect: “We give you a rating. If you don’t like it, we won’t publish it. If you like it, you pay us to print up thousands of rating cards and reports that your salespeople can use to sell insurance. It’s a win-win.”

The ratings process was stacked in favor of the companies from start to finish. They were empowered to decide when and if they wanted to be rated. They got a “sneak preview” of their rating before it was revealed to the public. They could appeal the rating if they didn’t like it. And if they still didn’t get a rating they agreed with, they could suppress its publication.

Three newer entrants to the business of rating insurance companies — Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Duff & Phelps — offered essentially the same deal.

But instead of earning their money from reprints of ratings reports, they simply charged the insurance companies a fat flat fee for each rating — anywhere from $20,000 to $40,000 per insurance company subsidiary, per year.

Later, Best decided to change its price structure to match the other three, charging the rated companies similar up-front fees.

Not surprisingly, the ratings agencies gave out good grades like candy. At A.M. Best, the grade inflation got so far out of hand that no industry insider would be caught alive buying insurance from a company rated “good” by Best. Nearly everyone (except the customers) knew that Best’s “good” was actually bad.

Despite all this, First Executive CEO Fred Carr was not satisfied with his rating from Best and went to Standard & Poor’s to get an even better rating.

Typically, S&P charged up to $40,000 to rate an insurance company. And just like the deal with Best, if the insurance company didn’t like it, S&P wouldn’t publish it.

But along with junk bond king Michael Milken, Fred Carr cut an even better deal. Milken paid an extra $1 million under the table and, in exchange, got a guaranteed AAA for his junk bonds and for Fred Carr’s insurance company. All this despite a business model that was predicated largely on junk bond investing!

Getting the insurance regulators to cooperate was not quite as easy. In fact, the state insurance commissioners around the country were getting so concerned about the industry’s bulging investments in junk and unrated bonds, they decided to set up a special office in New York — the Securities Valuation Office — to monitor the situation.

What’s a junk bond? The answer, as I’ve explained, was undisputed: Any bond with a rating from S&P or Moody’s of double-B or lower.

But the insurance companies didn’t like that definition. “You can’t do that to us,” they told the insurance commissioners. “If you use that definition, everybody will see how much junk we have.” The commissioners struggled with this request, but amazingly, they obliged. It was like rewriting history to suit the new king.

This went on for several years. Finally, however, after a few of us screamed and hollered about this sham, the insurance commissioners finally realized they simply could not be a party to the junk bond cover-up any longer.

They decided to bite the bullet. They adopted the standard double-B definition, and reclassified over $30 billion in “secure” bonds as junk bonds. It was the beginning of the final act for the junk bond giants.

The New York Times was one of the first to pick up the story. Newspapers all over the country soon followed. That’s when the large life and health insurance companies began to fall like dominoes — Executive Life of California, Executive Life of New York, Fidelity Bankers Life, First Capital Life — each and every one dragged down by large junk bond holdings.

And this was just the prelude to the biggest failure of all — Mutual Benefit Life of New Jersey, which fell under the weight of losses in speculative real estate.

Back to the Present

If you think Wall Street ratings agencies have learned some lessons from history, think again.

They still charge the companies big fees — for the ratings they issue to those same companies.

They’re still more concerned with protecting the companies (their primary source of revenues) than protecting the public.

Their ratings process is still riddled with egregious conflicts of interest and bias.

And as I told you, they have admitted their bias by quietly dropping the word “independence” from all their literature.

Next in this series: Massive ratings fiascoes in the stock market and how to avoid them.

In the meantime, if you haven’t done so already, be sure to visit the Weiss Ratings website. The info, tools and resources it provides are vast and 100% objective.

Good luck and God bless!

Martin

P.S. For your added protection, there may be a 3-second delay in accessing or site.